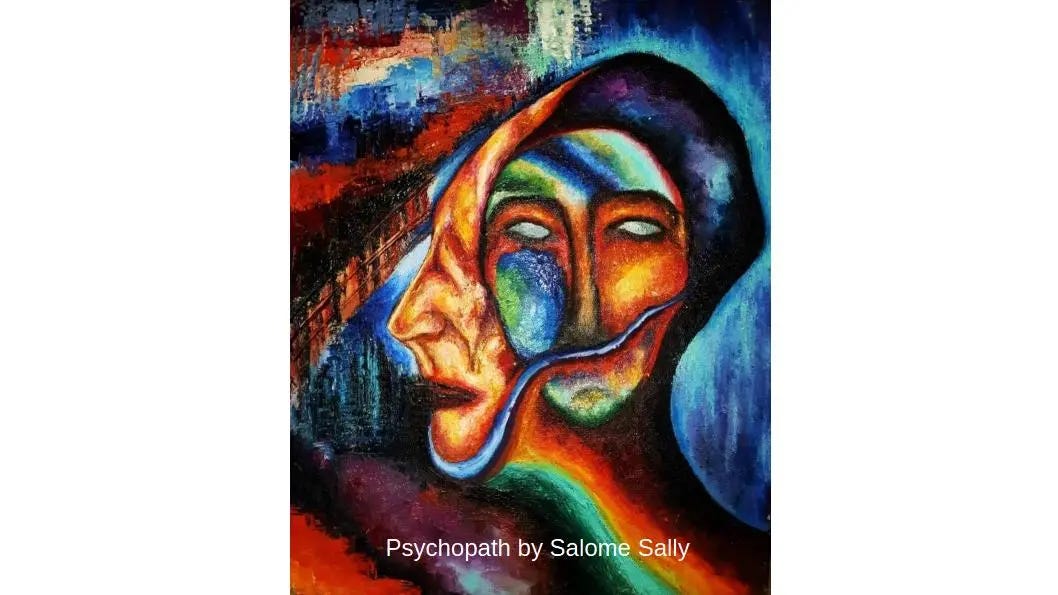

Companies have certain legal obligations and rights. They have no conscience, no moral code and no social responsibilities. That is the law in every country. Corporate social responsibility (CSR) is an oxymoron – it contains contradictory and incongruous elements. It is not lawful for corporations to give charity, other than as part of a deal from which the corporation expects to benefit. It is not lawful for corporations to sign up to commitments from which they will not gain. If a corporation had a personality, it would be that of an amoral psychopath.

How have we been seduced into believing otherwise? One reason is public relations and advertising. Beginning in the nineteenth century, companies used brand character, celebrity endorsements and human mimicry to encourage customers and stakeholders to invest trust and confidence, and to build a human-like relationships with them.

Another reason is the legal concept of corporate personhood that exists in every jurisdiction. This gives companies obligations – they can be sued for breaking laws; it gives them rights to sign contracts; and it makes them distinct from employees and managers. Corporate personhood does not give corporations any moral guidance whatsoever, other than compliance with relevant law. Insofar as a corporation benefits anyone other than the shareholders, it may do so only out of self-interest, albeit ‘enlightened’.

These self-evident, but often concealed, truths have been brutally exposed by corporations’ responses to a changing political and cultural climate. The fiction of the double bottom line has been dropped like a hot brick by companies like BP, Shell, BlackRock, Unilever, Crocs, Coca-Cola, Nestlé, Microsoft etc., etc., etc., that have rolled back their CSR agendas and reinterpreted them as risk management.

So how does it feel to work for a psychopath?